ABBOTTABAD

The town in Pakistan where Osama bin Laden was killed in 2011, as seen in this travel report from 1969,

a chapter from Peter ten Hoopen, High Across the Bedrock (Mobipocket ebook)

THE DESCENT FROM THE HEIGHTS of the Khyber Pass took us down into an abyss of regrets. We had left Afghanistan. And whatever lay ahead, it would not be the same. We told ourselves that we could always go back - but we weren't going back, we were going East. The first hamlets of the North West Frontier Province, home of Pathan tribals with their antiquated rifles, henna-red beards and rolled-up berets, cheered us up. There is something in change, movement, discovery, that lifts the spirit. Change rejuvenates and thrills. It is the essence of life, the purest manifestation of the forces of creation. It injects man with hope and gives him the strength to overcome the challenges of the unknown. Most importantly, it stimulates that tiny gland, hidden within the folds of our brains, that secretes the hormone of joy.

As our bus rolled into the city of 250.000 so aptly named Peshawar, 'Frontier Town', we sat upright in our seats. We were now entering the former British India, cradle of one of the world's oldest and most intellectually advanced civilisations. The Indus culture of four to three thousand years ago had better amenities than Europe in the Middle Ages and better than many Asian towns today. Indian thinkers of the first millennium before our era formulated a transcendental philosophy so lucid that illiterate villagers can grasp it. They did this with a poetic elegance that survives to the present day and has helped Vedantic philosophy become the world's fastest growing spiritual movement. Around the year 1000 the Mughal invaders came from the Sind and across the Khyber and imposed Islam. Their hold on the land would last for eight centuries, their hold on the minds of the people continues to the present day. The British domination was just an interlude, be it an interlude of two centuries. The British left a civil service, an infrastructure and a language that provides access to the world - a useful heritage. But apart from hockey, cricket and college ties they did not leave much that is loved. The most widely appreciated music is not 'God Save the Queen' but the Sufi inspired Persian ghazal, the love song for Allah that Shah Jahan and Akbar had performed at their courts when they were tired of the dancing girls. The separation from India, shortly after World War II, has left this lobe of the subcontinent cut off from much of its heritage. To any but the Pakistanis themselves, the loss would seem great. Not just because they miss access to Delhi and Lucknow and Ajmir and all those other cities with a strong Muslim presence, but also because their minds have been shuttered, shielding them from the diverse ecumenical world that is India. In their prayers, Pakistanis turn their backs on India five times a day.

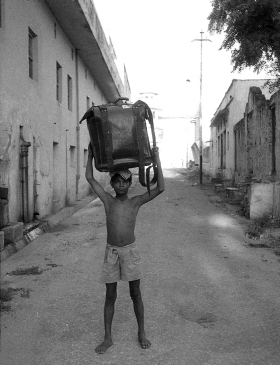

Peshawar left no doubt: Pakistan, try as it might to dissociate itself, was still India. The world of rickshaws and tea-stalls, beggars and Assistant Superintendents, ladies in silks and lepers in rags, stalking touts and pious Hajis, mangy dogs, buffaloes in back yards and goats on balconies, white bungalows on tree-lined avenues, towering cinema posters and people hanging off buses - the overcrowded but cosy, intensely human India. We were on our feet, rambling through the bazaars, from the moment we got up till the moment we crashed. This was a city that stuffed you with impressions - and sucked you dry. No need to do anything, just being there was all it took. Peshawar survives as a maelstrom of floating images, rich in saturated colours, smells that made me breath deeper one moment and shallow the next, a euphonious cacophony of taxi horns (could that one be our old 180D?), shouts of hawkers and shards of film music, and flashes of faces that took only 1/125 sec. to be written indelibly on the brain's sensitized material. For the first time, more than just a few beggars. Everywhere we look sit, walk, limp, lie and crawl dirt-covered beggars: naked and half naked children, some too young to talk, with deliberately broken limbs that have grown into horrible deformities; old men with white beards and arms like sticks; a man with gaping red holes instead of eyes, nose and mouth; men without legs who propel themselves through the crowds on flat little trolleys with roller-skate wheels; an old woman in tattered rags who scurries around nervously among her collection of garbage and wrecked furniture, a writhing mass of flies covering her face, hands, clothes and hair; a neckless man whose open shirt reveals how his chin grows out of his breastbone. Between them stride tall, proud Pathans with noses sculpted in granite; Punjabis with Aryan features and Mediterranean complexions; darker, finely built Sindhis and wiry Kashmiris; tribals from Chitral with the tripping eyes of mountain people in town, and discriminated yet stuck-up Anglo-Indians. The women, a few survivors of an earlier age excepted, wear no veils worthy of the name, just filmy scarves that serve coquetry better than modesty. It is a delight to see their pretty curved noses, dark gleaming eyes and glittering white teeth. It is as if the graves have opened and half the world population has risen from the dead. Apart from these wonders, there is an astounding wealth of bizarrerie. An old man with a coffee-black complexion wears an enormous white moustache that cuts his face in two like a thick white line. He rounds a corner and bumps into a pale-faced boy who has glued on a large black moustache. No course teaches you what humanity is, better than walking around in a South Asian city and observing the roles people play. This is life in the nude. The rich live in palaces with more servants than the Queen of England, send their kids to Oxford and take their wives shopping for emeralds at Bulgari. The poor sit in the dust and scratch their fleas. The bastards have few scruples to surmount and no rules to worry about; the law does not fetter those who own the judges. The pious have to overcome so many temptations to be selfish and improve their lot that those who succeed even marginally soon come to seem saintly. The extremes are horrible, but enriching. Living in the face of death is not easy, but it makes you feel keenly alive. As we strolled through the swarming streets I could sense my soul staying close to my body. He liked it here.

The Pakistanis drank tea with milk, a form of suffering imposed on them by the British. Milk binds the tannin, dulls the colour and makes even the most refined brew taste like a spoiled dairy product. Yet in former British India people persisted in the following recipe: pour half a cup of water and half a cup of milk into a saucepan, throw in a spoonful of sugar and a pinch of Brook Bond dust tea (the crushed leaf fragments that plantation owners sweep up from the factory floors and sell to the English), bring to a boil and cook till the foam rises to the rim; pour through cloth and serve. I was not going to even try this. So every time we entered a tea stall, I had to explain how I wanted my tea. Actually, 'explain' is not the word, as it suggests that the intentions become clear in the end, which was never the case. Often I had to physically restrain the tea stall owner at the moment he dipped his ladle into the milk pan. 'Dud, nay!' After a few weeks I could state my wishes in complete sentences, but even then I often had to request access to the implements and ingredients and prepare my own. The result was hardly commensurate with the effort. It was still cooked Brook Bond. But result isn't all that counts in life. There is also principle. It was only half a year later, when I got to drink tea with butter, that I decided milk wasn't so bad after all. In other respects our acculturation proceeded apace. Resting on a bench in the town park, we were joined by two Chitralis of about our own age. Dark, lanky fellows with eyes that radiated freedom, confidence, and contempt for the imprisoned townsfolk. In the time-honoured tradition of their tribe they offered us a smoke. It was good shit by Pakistani standards, but so soft you could crumble it without warming. Ewald pulled the piece apart, stuck it together again like putty and gave it back. 'That's nothing. Don't smoke that.' He took out our Kandahar produce and bit off a chunk: 'Here, this is real charas!' They emptied a Craven-A and refilled it by sucking the hash up into it, a technique that requires lungs as powerful as a late model Hoover, took a few drags and for a minute just stared into space to evaluate the effect. 'Rubbed by hand?' 'Yes sir.' 'No ghee?' (Pakistanis often add clarified butter as an emulsifier.) 'No sir.' 'Oh, very good... You sell?' 'No sir, give only.' We spent the rest of the afternoon with them and went through their whole packet of Craven-A. (Cigarettes were marketed in packages of ten so the lower classes could afford them; even so, most working men could only afford to buy one or two at a time.) Our new friends invited us over to their village, three days travel up the mountains, and we were seriously tempted; but India, only three-hundred miles away, proved too strong a magnet. No more side-shows now, but on to the main attraction. The train could get us there in one day. But Pakistan grabbed us and let us stay longer than planned. Come to think of it, few places on earth have ever made me leave early. Many have made me stay well beyond the time I had allotted. It is the lover's affliction: never sated, ever eager to linger.

Pakistan was born, not of love, but of fear. When, shortly after the end of World War II, the British were about to relinquish control over the jewel in their crown, the Indian Muslims, associated with the Mughal conquerors, feared that the massive Hindu majority, soon no longer restrained by the European power, would seek retribution for eight centuries of sometimes cruel, often insensitive Muslim rule.[i] This fear, whipped up into a frenzy by their religious leaders, led Muslims to attack Hindu neighbourhoods and slaughter anyone they could find - thus provoking Hindu acts of revenge that 'proved' the Muslim fears correct. Mahatma ('Great Soul') Gandhi, the prophet of non-violence, struggling to keep the India he loved together, did what he could to reconcile the Hindu and Muslim communities. He had stated repeatedly: "You shall have to divide my body before you divide India". But his Muslim adversary, Muhammad Ali Jinnah was equally adamant: "We shall have India divided, or we shall have India destroyed." Not surprisingly, the rabid would defeat the meek. Formed August 15, 1947 by cutting off India's Eastern and Western wings, chasing out the Hindus and shunting in as many Muslims as possible, Jinnah's Pakistan had yet to prove it's viability as a nation. (It would prove its non-viability in 1971, when the Eastern part claimed independence and, after a bitter war, became Bangladesh.) The lack of cohesion of this artificial country, this Muslim reservation, had shown itself in a steady erosion of democracy. When we arrived it was ruled by Field Marshal Ayub Khan, who had just declared martial law. Popular nervousness was palpable, dissent was rife. When we entered Rawalpindi, a city of three-hundred-thousand, there were mobs on the street corners, yelling for change - nasty echoes of the mobs that had led to the creation of the country. In the centre the bus had to make a detour because youths were throwing up a barricade of refuse, rubble and overturned rickshaws. When our driver, like all motorists annoyed by anything impeding progress, yelled some abuse, stones were hurled at our vehicle, hitting the flanks with dull thuds. The driver, not concerned about dents to a vehicle that did not belong to him anyway, laughed heartily and honked his horn to further whip up the emotions. Near the bus station other mobs walked about under huge banners, all of them in Urdu, which alas is written in the Persian alphabet. We asked the driver what they meant, but either he was illiterate or he didn't want to tell, embarrassed by anything that might be perceived as a shortcoming of his country. Nearly all the shops were shuttered; at the few that remained open the owners stood ready to roll down the metal at the first sign of trouble. On street corners huddles of policemen stood leaning on their lathis, looking vulnerable in berets, shorts and sandals. The bus swung off the main thoroughfare and stopped in front of a four-story building. The driver turned to us: 'This is your hotel'. We had not informed him about our plans for lodging, nor in fact did we have any. We stared at him speechlessly. 'Streets very dangerous now. This place more safe. They can provide meals in your rooms.' How thoughtful, he had found us a sanctuary. We thanked our protector, climbed on to the roof to retrieve our bags and hurried inside. The reception was crowded with men mulling over the news. 'What is going on', we asked. An elderly man in a grey suit with glasses took it upon himself to answer: 'We are having general strike. All businesses shall remain closed. 'Tomorrow also?' 'Yes, definitely. Tomorrow also no business.' He seemed to regret the loss of turnover. 'What exactly is the problem?' A man in a blue blazer, younger, but working on a stoop, intervened angrily: 'Problem is Ayub Khan. People not happy with Ayub Khan.' 'You want Ayub to step down?' 'Some people want.' Outside we heard the syncopated yell of the mob: 'Ayub-Ayub! Ayub-Ayub-Ayub!' 'What about you?' A nervous giggle ran through the assembled. Realizing how much he had exposed himself already the young man declined to answer. Several of the assembled shot around glances as if trying to ascertain who might later turn out to be the fink. The elderly gentleman wobbled his head soothingly to reduce the size of the problem: 'Maybe Ayub is a good man... But maybe not good for the country.' 'You think he should leave?' The man seemed to overcome some inner resistance, straightened himself and spoke with the full weight of his position: 'Yes, he must. But he cannot go today. If he steps down now, he will be the laughing stock of the country.' A soft murmur of consent filled the reception. 'So as long as the strike lasts, he will last?' 'Yes, definitely.' 'And as long as he stays, the strike will continue?' 'Yes, definitely.'

The man in the blue blazer got us a room on the top floor with a view of the riots. In view of the uncertain future we decided to test the room-service straightaway. Soon we sat on our balcony munching freshly baked bread with chilly spiked omelettes and jam, while observing how the mobs below taunted the police, throwing stones and rotten oranges. It was not an appetizing sight. Those mobs looked vile. Maybe it was their age. Some of the more violent consisted only of kids below sixteen. To see them lighting bonfires in the middle of the Mall, throwing in windows of passing cars and banging the metal shutters of shops with sticks, was deeply frightening. It is one thing to see miners or blast furnace workers go on a rampage for improved safety or better pay, and quite another to see those immature creatures go on the rampage. You cannot argue with mindless violence and there is no known defence other than greater violence. That first day in Rawalpindi we did not leave the room, except late in the evening, when most of the kids had gone home and a few daring tea stall owners had opened up shop for the benefit of the populace, who badly needed a place to gossip. The second day was more violent. The mobs were larger and the police came out in full force, made lathi charges right beneath our balcony and bashed in some faces. In the day-time we did not dare leave the hotel - if only because the receptionist had heard on the radio that two other Westerners had been beaten up on the streets. It had also been raining, a circumstance that sapped our courage. In the evening we sneaked out for a cup of tea, found yesterday's tea stall closed and ventured out a few blocks, trying to locate one that was open. We had just spotted a promising light at the far end of the street, when out of an alley about hundred yards away flowed a group of adolescent Rawalpindians who yelled the by now familiar 'Ayubayubayubayubayub'. The one in front carried what looked like a huge torch in the shape of a cross. We stood puzzled: a cross-burning in the heart of Pakistan? As they marched toward us the refrain rang again: 'Ayubayubayubayubayub!' Then it hit me: they were burning the Field Marshal in effigy. When seen on television - president Johnson, general Thieu, dictator Franco - it had seemed such a harmless pastime. Now it was sickeningly real. As for the emotions, there was no mistaking: this was murder. The flames suddenly flared up fiercely, setting the head ablaze with russet hair. A loud howling rang through the empty streets, ricocheting off the galvanized iron shutters. When the puppet started to fall apart it was thrown on the ground. The boys pushed each other aside for a chance to trample the corpse, sparks flying in all directions. We stood with our backs pressed to the façade of a building, in the shadow of its awning. Still, we were hardly invisible, particularly as there was no one else on the street. The youngest boy discovered us. He let out a yelp to alert the bigger boys to this wonderful new target. They surged forward as one body, cheering like a winning team. We took off like rockets, fired by fear. There is no better fuel. Although we had had nothing to do all day but sit and stare out the window, we ran a winning 800 meter dash. At the corner to the hotel we slowed down just enough to get a good view of the competition and saw that the nearest boys were fifty yards off. We kept running and managed to get inside before the first pursuer rounded the corner. Not taking any chances, we raced through the empty reception, up the stairs, opened our padlock with pounding hearts, closed the door behind us and with a rush of relief bolted it shut. Pulling the curtains shut, we peered through the cracks and saw the boys search for us in the neighbourhood, looking everywhere but up. The third day brought further escalation, with a car being burned on the Mall and shots fired in the air. More and more troops had entered the city. Not just police, but army as well. The massive force appeared to have given the mobs a better focus. Fewer bands roamed the streets to look for trouble, as there was enough of it around. By lunchtime a pitched battle was being fought on the Mall right in front of us. Fed up with our limited room-service menu we decided to risk a raid on the bazaar behind the hotel, where it was relatively quiet now and several dare-devils operated their shops with the shutters half closed, or half open, whichever way you looked at it. We picked the nearest one, ducked under the metal-work and found ourselves in a busy fruit stall. A dozen men stood pressed together amongst the pyramids of pears and polished apples, heatedly discussing the events of the day. The elderly gentleman we had met the first day sat on a crate, feeding himself slices of banana that he cut off with a penknife. 'Ah, there you are my friends! So you are still here in Pindi?'

'We wouldn't be if we could get out safely.' 'Ah yes, this is some tight spot you are in. You better come with me to Abbottabad. I am leaving this very afternoon.' Abbottabad? Where was that? And didn't they have the same problems over there? The gentleman deftly threw the banana peel out through the opening below the shutter and smiled patronizingly: 'Big town, big problems, small town, small problems. You will find Abbottabad very small. A hill station, highly civilized. It will be to your taste.' We had heard about the hill stations. Resorts in the mountains that the British Raj built to escape the heat of the plains in summer. It was mid-winter now, but we found much appeal in about a resort town off-season, not the least of it the guaranteed absence of a crowd of holiday-makers. 'How do you go there?' 'My driver will take us.' We needed little time to make up our minds. Anything was better than to be cooped up in our hotel, waiting out the stand-off. 'I shall pick you up at two o'clock sharp.'

We would later learn that the Pakistani and Indian middle-classes were always making appointments at some time sharp. What it meant was 'probably sometime after, but certainly not before'. Our friend arrived at four. In a shiny black Austin Cambridge with cracked leather seats. He was as welcome as if he had come at the appointed time. Maybe they are right in keeping their schedules flexible. If someone is important you welcome him anyway, if he isn't you let him wait till a moment that suits you. We got out of town without the least obstruction, made a swing through Islamabad, the modern capital of Pakistan that we had planned to skip but that our host was mighty proud of, and found that our finely honed sensors for grace and charm had not let us down. Whatever they built this town for, apparently not to live in. But then, we were still suffering from this romantic notion of towns as organic growths, like the old towns of Europe, like Shiraz, Kandahar, Peshawar. (The affliction has proved chronic. It even gets worse over time.) The ride up the hills was pretty in a way that we had not encountered before. Lush greens hills with villages nestled in the vales and clinging to the slopes, orchards and meadows and rushing brooks, little white mosques, flocks of sheep and roaming cattle... 'Picturesque', that word full of false sentiment, was crying for a new life. (Clichés are like banana trees: the only way to rejuvenate them, is to chop them off at the root.) Abbottabad turned out to be a small English town in a Pakistani setting. Bungalows and cottages, churches and schools and hotels that seemed transplanted straight from Sussex. Hotels that evoked the horrors of breakfast with kippers and eggs with fried kidneys. Our host, Moussa Latif Jandial, turned out to be the director of the local Grindlays Bank, well connected in the hospitality trade. He arranged us a room in a mock-Tudor villa a little outside town, straddling a ridge. It charged a paltry low-season rate and was blessed with a vue imprenable across the valleys and the distant Pir Panjal range. The name rang a deep bronze gong: who was this Pir Panjal? A Sufi Saint of old who had retreated in the mountains? On the way back into town for dinner I asked Moussa. He didn't know, but he knew about the Sufis. 'The Pirs are very popular still with the common folk. They are credited with miraculous powers and are believed to protect them from usurpation. Some of them are cheats of course, but most I think are good people. Actually, I don't know too much about them.' 'You're not a religious man?' 'Yes, but I was brought up in Christian schools.' 'Oh, you're Christian?' 'No! I am a Muslim, and always will be. But I was taught to use logic. There is no logic in the work of those dervishes. They make all kinds of claims, but cannot substantiate them. Muslims have no need to strive for the supernatural. All we have to do is submit our souls to Allah. We should never be arrogant.' 'The Sufis are arrogant?' 'They are very clever people. Therefore they think that they can place themselves above the law.' 'We are Sufis as well.' 'No, you can't be, because you are not Muslims.' 'Sufism is older than Islam. There are Sufis who have adopted Islam, and others who have not.' 'That, my dear young man, is sheer heresy. Even the Sufis themselves admit that you cannot be a true Sufi if you are not true to the ulama.' 'You know why they say that? Because otherwise they would get their heads chopped off. Saying that is their armour.' 'I have never heard of that.' Moussa stared out the window as the car wound up the narrow road. 'Maybe you're right', he finally admitted. 'One of my best friends is a Sufi, and he pretends to be a prayerful Muslim, but I've always suspected that he's a freethinker.' 'You don't like freethinkers?' 'Oh, I do.' He turned around to us and smiled: 'But they are very dangerous.'

We were just finishing our meal in a local eatery for the better classes (probably having phirni, a pudding of rice flour garnished with chopped pistachios, cardamom and sometimes silver-leaf) when a young white male with a flossy beard and a Pathan beret drifted in for tea. The boy was hardly eighteen and he had a complexion so pale that I worried what he was doing so far from home. He introduced himself as Nur-ud-Din, but readily admitted that his real name was Robbie. His accent had the ring of the home country. There was no mistaking even the town he was from. If it wasn't Rotterdam proper (Feijenoord-supporters) than Rotterdam-South (Sparta). Robbie spontaneously told us that he was living in a Sufi monastery up in the hills and enjoying it much. There you go. You search for them everywhere and then, without even looking, you walk straight into their arms. The seeking makes the finding impossible, and only by ceasing to seek can the finding take place. Absolutely classic. 'The food is very good. I am the cook.' Tasty food must be very important for the development of the inner life. It does wonders for the spirits of ordinary men, so why not of saints? Moussa saw our growing enthusiasm and I could sense a beginning of irritation. I thought he felt neglected, and tried to involve him in the conversation, but he remained sullen. I apologized: 'Sorry Moussa, but this is such a coincidence, this boy is from the same country, and he has, eh - ' 'I shall leave you with your friend now. Maybe we see each other again. I have my meals here everyday. Sometimes tiffin also.' 'I'm sure we'll see you again then, Moussa. Thanks very much for the ride.' Ewald walked him to the door, taking him by the upper arm like a son his father. I saw them exchange a few serious words. 'What did he say?' I asked when Ewald got back. 'That we did not know the first thing about Sufis, but that we would soon find out.'

After an extensive English breakfast of orange juice, oatmeal, fried eggs (without the feared innards) and toast with marmalade, tea and milk served separately, we walked out of town to the monastery of our friend. It was half an hour along a lovely winding road that made monastic life seem not only attractive, but imperative, the natural thing to do. The monastery turned out to be a two-story house, built of brick, with two wings projecting forward. On the courtyard in front was a small formal garden, laid out around the well. The roses, well pruned back, were hesitantly beginning to sprout. It was very silent. There seemed no one about. It was not a place to go knocking on doors or yelling out names. We walked around the building, peered into open doorways and finally found our little galley boy in the Southern wing, in a dark kitchen, his arms deep in the sink. He apologized, but said he could not make time for us before this work was done. Could we wait outside? We sat on the rim of the well and stared at the clouds drifting North over the hills, the ordered chaos of ant life, and at the flower of a banana tree, tossed about playfully by a gentle breeze. There was a smell of fertile earth and young life. After half an hour, when the dishes were done, we were joined by Nur-ud-Din, whom I mentally kept calling Robbie because looking at his wan, withdrawn countenance, 'Nur', 'Light', was not an association that came to me naturally. He did come across as a real recluse though, someone who has been out of this world for a while. As we talked longer, an inner voice began suggesting that he must have been out of it before he even left Rotterdam. But maybe that was Moussa's voice, not mine. Robbie told us his whole life story, which being short and uneventful, may be summarized by saying that he had dropped out of school, got into reform school, dodged the draft and while trekking along Jugendherberge in Bavaria had run into this great Sufi master, a German man in his mid-forties, who had initiated him into the order and taken him along to his settlement in the foothills of the Himalayas, to be groomed for missionary work among the Pakistanis. There were twelve other students, about half of them local boys, the others mostly Germans. All of them were away now on various evangelical missions. Only the Master and he remained.

Robbie had arranged an audience for us at noon. Pir Firdausi, 'Master Paradise', received us in the library, a large room with bookcases from floor to ceiling and French doors that provided a heavenly view of the hills. It smelled sweetly of aging paper, mixed with a faint, sweetish perfume like drying wild flowers. Pir Firdausi got up to greet us, a tall man dressed in a brown habit with thin, shoulder-length hair. His eyes had a peculiar radiance, and his movements were quick and angular, which rather emphasized his limp. He spoke with a heavy German accent that sounded like Ruhrgebiet. 'Your friend Nur-ud-Din tells me that you are interested in Sufism. That is very good.' We admitted the excellence of our interest. 'The spiritual journey is like a mountain path. It leads to great heights, but...' Pir Firdausi sought out our eyes and stared at us menacingly. 'But it is fraught with peril.' I saw Ewald smile at that bookish phrase. 'In the world of the spirit, as in the Alps, it is extremely important to find a good guide. It's a matter of life or death.' He paused to let his words reverberate. Pir Firdausi spoke English with difficulty. You could sense that he was translating German phrases as he went along - which almost forced me to reconstruct his mental original: 'Es ist äusserst wichtig sich den richtigen Führer zu finden.' 'Wir können ja auch Deutsch reden, wen Ihnen das leichter fällt', I said. He jumped at the suggestion. 'Of course, let's speak German. These ideas are easier to explain in our own language.' Since when was German our own language? Hadn't the Pangermanic notion been somehow refuted by the early dissolution of das Tausendjährige Reich? 'German is the language of philosophy. We have always been thinkers, haven't we? Spinoza, Kant, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Heidegger... And great poets, Goethe, Schiller, Fontane - that is why we can understand Sufi poetry so well. There is a resonance to which we are finely attuned. We have this inborn sensitivity, refined through our culture, which allows us to transcend the literal meaning and grasp the essence.' He was getting good. Though I did not feel that this inborn sensitivity was anything exclusively Germanic. 'But the intuitive approach has been refuted repeatedly by the great Sufi masters. Intuition leads to the morass and the landslide. One moment the light may be seen, the other moment it may be obscured. By contrast, the light of the Pir, the Murshid, shines at all times. That is why the line of murshid-mureed, teacher-disciple, must never be broken.[ii] It is like the line we use in mountain-climbing.' He used 'klettern', a world, that if taken as an onomatopoeia, suggests something hard falling off the rocks. 'To arrive at the top safely, you must follow the rope set out by the guide.' Again, that 'Führer'. I made an effort to dissociate the language from its past, the man from his language. 'Alas my son, good guides are few...' Pir Firdausi leaned back in his chair. Enough said. After half a minute the Pir realized that we were too comfortable with silence to break it, and were glancing past him at the hills - partly wooded, partly meadow, the image of Arcadia. He stood up, turned to the French doors and looked out, positioning himself in the centre of our view, the light behind him pouring a radiant halo around his figure. Suddenly he turned: 'Nur-ud-Din is very fortunate.' The question 'In what way?' hung in the air between us. You could see it flutter to stay up. Pir Firdausi seemed to regret that it failed to get uttered. But we did not need to ask. We knew the kid was fortunate. He was not in jail and he ate well. 'He has found a teacher who has helped him to rise - from nowhere! - to the state he is at today. He is not perfect yet, I am not saying he is, but his devotion is complete. It is touching to see. He has no ego left. He has given over his whole being. A state of great grace... I am very proud of him. Like he were my own son.' We smiled at this endearing simile. We actually felt somewhat paternal towards Robbie ourselves. 'Of course he has his limitations. He shall never be a great guide himself. But greatness is not what we are after. We are only after the Truth.' I looked at Ewald. Was that what we were after? We got up and joined Pir Firdausi at the doors. 'Could we open them?' Ewald suggested. 'By all means. God has given us another glorious day.' He had. It had rained at night and masses of grey and black cumulus were racing through the sky, whipped up by a firm breeze. Patches of meadow and forest were set aglow by golden shafts that shot through the shield of clouds. We went outside and stood on the paved terrace, three men open to the universe. It was one of those views that you can keep staring at forever. Pir Firdausi seemed sincerely moved. 'Why don't you stay here a while? Most of my students are away... Take one of the rooms upstairs. You are welcome to join us in our little observances if you like but you don't have to... You are free to do as you please. And Nur-ud-Din is an excellent cook.' That settled it. 'He does a really authentic mutton biryani - not quite so spicy of course - and very good German, I mean European food. 'No pork steak, of course, ha-ha!' 'Kein Schweinsbraten, ha-ha!' It was tough, but where did we hear this said, 'Every cripple has his own way of walking.' I noted early in life: in making friends you can't be too choosy. Jesus himself had to content himself with a bunch of fishermen. 'Thank you. We gladly accept your invitation.' 'If you want to know more... You know where I am.'

We ambled back through the hills, loaded our bags into a ghadi, here called a tonga, and departed for our retreat, making a long stop halfway to rest the horse and chat with the driver. 'Pir Firdausi was sent us by Allah', he opined. 'He is very strict - some say too strict - but that is exactly what young men need.' We arrived just in time for the late afternoon snack, a good British-Indian custom, kept alive by those that can afford it. Mixed vegetable samosas, papadams, and a titillating fresh chutney, washed down with nimbu-pani, a lemonade of limes. We were given the room over the library, with that same, paradisiacal view. I wondered if my reserved attitude had not been unjust. Pir Firdausi was served dinner in his private chambers, next the library. We had ours with Robbie in a room off the kitchen that served as canteen. After the pudding we invited Robbie over for a chat in our room. He declined a smoke, said that he had never liked it; he had tried some opium once in Rotterdam, in the old seamen's quarter of Katendrecht, but it had made him sick. He couldn't stand liquor either. Had drunk a lot when he was younger, but invariably ended up lying in a gutter somewhere. Five gins and he was gone. Actually didn't take coffee too well either. It gave him palpitations. I started worrying about his heart. But maybe it was just his sensitive nature. He seemed like a naked baby. Utterly defenceless. I realized that he had never been loved. That his whole being was crying out: 'Hold me!' But we were not in a penny novel. 'Pir Firdausi is a great master. I love him very much. He has done so much for me - and for many other people. The people in the village here think that he is a saint. He gives money for schools and gets boys up here for languages classes, he helps the parents of the boys in the college and participates in many projects with the government. He has set up a national program to teach young students about the true values of Islam and opens the door to those that want to pursue the path of Sufism.' 'Aren't the Pakistani Sufis perfectly capable of doing that themselves?' 'They are degenerates. They do not teach the proper path. Purity is essential.' Did we hear the word 'Reinheit?' 'That German aspect, doesn't that bother you?' 'Why? I don't know German. We only speak English. And Urdu. He speaks excellent Urdu.' 'You know Urdu yourself?' 'Sure, it is part of the curriculum.' He spoke a few sentences. That same whining accent, but confident enough. We asked him to teach us the basics. With all pleasure. Tomorrow after breakfast we'd start the first session. But now he had to retire. Pir Firdausi's spiritual discipline called for early morning meditation, preceded by a bath and cleaning of the room. His alarm stood at four. We were glad that our ambitions for spiritual advancement were limited and sat staring at the starry night for hours, silent and in peace. As Ashtavakra said to his royal pupil Janaka some three thousand years ago: 'Millions hunt for worldy pleasures and thousands aspire to enlightenment, but only a precious few strive for neither and are at peace with themselves.'

We had been in Haus Firdaus three nights when Robbie asked if we didn't mind being alone - and without catering - for a day. Pir Firdausi was away for official business in Islamabad, and he himself would take the day off to search for size 11 shoes in Pindi. According to the radio, the riots were still going on, but as he dressed in local style, Nur-ud-Din thought he had little to worry. We told him to feel free, decided to fast till he was back and made ourselves comfortable in the library. Reference works and studies on Islam, Sufi poets in translation, works on Islamic art, dictionaries... At least two thousand titles. Most seemed to have never been opened, leave alone read. On opening they made that soft crepitating noise that stimulates the book-lover's erogenous zone, the foreplay to deeper pleasures. It seemed as if someone had decided what needed to be there, ordered the lot of it, unpacked the crates and stacked the stuff on the book-shelves. 'Let's see what he has in his own room', Ewald said. (I am not assigning him the initiative to shift the blame, but to credit him.) The door was not locked. It was a strange room. Disorderly, but cosy. Eclectic and 'mysterious' in the sense of: 'The door creaked open and they entered a mysterious room...' A four poster bed with pale brown mosquito nets draped over the frame; a print of Burak, the winged horse that carried Muhammad to heaven; a bust of Beethoven; a crucifix and an Indian string of holy beads with a swastika pendant, symbol of eternity; a photograph of an old Persian murshid, dressed in a silk robe, sitting on a throne; a small roll-top desk of polished red teak and a large bookcase. The titles here were different. 'Volk und Sippe.' 'Die Judenfrage.' 'Mein Kampf.' 'Die Endlösung.' 'Der Führer spricht.' 'Die Wahrheit über Zionismus.' 'Die Fahne Hoch!' 'Arabische Friedenspolitik im Mitten Osten.' 'Palestina: Land und Volk.' 'Der grosse Lüge' (a refutation of the pernicious lies about Auschwitz), and a lone English study: 'The Zionist Conspiracy.' We were sprachlos. All the books had been annotated, most with crude, uncontrolled handwriting. 'A shame!' 'Pigs!' 'Murderers!' 'Zionismus = Zynismus.' Whole paragraphs had been underlined. In a tract entitled 'Awake': 'The Jews are to be congratulated on the success of their deceit. Not only have they managed to destroy the Great German Reich, but they have even managed to make the world blame the German nation itself. If this isn't chutzpah, what is? It is imperative that we show the world, particularly those parts of the world most suffering from Jewish usurpation, that we shall not forget.' The words 'Jew' and 'Jewish' had been crossed out as if even the existence of the words was blasphemy. We did a quick calculation. Yes, he was of the right age, he could have been there. In the Hitlerjugend at sixteen. And God knows where at twenty. We picked up a small atlas, the kind that they use in German high schools. Flipping through the pages to find the Middle East and trace our trajectory, we saw that something strange had happened South of Lebanon. Where Israel was supposed to be was just a black whorl. Someone with a ball-point pen had scratched and scratched furiously, with great pen pressure, till the whole state of Israel had been obliterated from the map. We stood trembling on our feet, barely able stand the intensity of the hatred that stared us in the face. 'My God, this guy is sick!' Ewald threw the atlas on the floor and walked out into the fresh air. I followed him out, seeing the whole scheme in a flash: training young Pakistanis to hate the Jews and send them out into the Islamic world. The final solution. With clean hands. We packed our bags, left a note for Robbie, suggesting him where to look for further info on his Pir's beliefs and trekked back to Abbottabad on foot, carrying 30 kaygees each, but feeling light with relief.

Given the strenuous

portage we just put in, the fast we had earlier decided on seemed unreasonable.

In the restaurant, Moussa was in conference with some of the town's other

notables. When we finished the meal he came over to our table. 'So how are your

Sufi friends?' 'The boy is

fine. He is buying shoes in Pindi.' 'What about the

Sufi master - did you get to meet him?' 'He is not a

Sufi, you know that. He is a Nazi. He and his organisation are brain-washing

Pakistani youth to make them hate Israel.' Moussa chuckled.

'That doesn't sound like hard labour.' 'The man is sick,

Moussa. Badly sick. You should see his atlas. He has crossed out the entire

state of Israel.' 'Ah, a symbolic

action. Apparently he is becoming more Pakistani already. We are very fond of

symbolic actions.' He smiled. 'This is our weakness.' To the traveller,

the greatest luxury of the Indian subcontinent are books in English, on a wide

range of subjects. No other former colony has so much intellectual life still

carried on in the language of the former overlords.[iii] This makes

politics and culture easily accessible, allows one to partake in the public

debate, and provides plentiful opportunity to laugh yourself silly. We had undergone

a traumatic experience and there is nothing more medicinal than a restrained

indulgence in self-pity. Since no pudding or cake can make life as sweet as a

new book we sacrificed desert and strayed into town to find a bookshop. I was

particularly hoping to find an early edition of Kipling, Maugham, or Conrad.

Something to read with a view of the hills. The English must have left tons of

that stuff behind and not all of it could have moulded away. We were mentally

transporting ourselves back to the days of the Raj, when we heard distant

shouting. A hockey match? The mob? Here too? No it could not be. This was such

an utterly decent resort. One could not imagine the populace rioting - except

perhaps over shortages of white table-cloth. We walked on in

the direction of the noise, but warily, ready to run back. We rounded a corner

and found ourselves at the fringe of a surging crowd. It was not your ordinary

mob. Some three-hundred well-groomed young men, most dressed in dark blue

blazers, a few in white cricket pullovers, stood shouting at the air and waving

fists. 'Ayubayubayub'

was popular here too. White sheets with black lettering were waved over the

well-trimmed heads, but too wild to be read. Suddenly a new sound broke out

from the centre of the crowd, a loud, raw cheering. We craned our necks to see

what was going on, but saw just a sea of bobbing black hair. A dog, probably

caught in the melee, was barking in panic. We climbed up the five steps of a

pharmacy, joining some middle-class citizens who had earlier availed themselves

of this elevated venue. There was a

whirl in the nucleus of the crowd, the cheering rose in pitch and with a burst

of energy some arms shot up in the air, holding aloft a white dog with black

spots. The dog tried to snap at the arms that held him and whined like a pig

led to slaughter. 'Ayubayubayubayubayub!'

Sure, but what

had the poor dog to do with it? Then we noticed the pattern in the black spots.

Four crudely painted letters: A-Y-U-B. 'Ayubayubayubayubayub!

'Oaaaah! Oaaaah!

Oaaaah!' The dog was

carried off in procession. As we had been spotted already anyway - pokes in the

ribs, muffled giggles - and no one seemed to suspect us of being Ayub

supporters, we followed the mob through the streets. The same streets where

only twenty-two years ago the British Assistant Superintendents had taken their

wives on evening strolls (the Superintendents would have been higher up, in

Simla or Darjeeling), sniffing the invigorating mountain air and the

disinfected, de‑Indianized ambience. We reached a

group of government offices. The cheering, which had dimmed somewhat during the

march, soared to a beastly roar, such as may be heard at hockey matches when a

penalty is scored. We elbowed our way through the crowd and climbed onto the

box of a tonga that was caught in the demonstration, helped up by the

hopeful driver. Looking down we saw that the dog had been lowered to the

ground, but was presently lifted up slowly by four young men, two holding its

forepaws, two its hind-legs. They leaned back against the wall of their peers,

braced themselves and pulled with all their might. The dog let out a long moan that

seemed almost human. 'Ayubayubayubayubayub!

'Oaaaah! Oaaaah!

Oaaaah!' A fore-paw came

off in a spray of blood. The young man who had severed it waved it over his

head like a sports trophy. Blood was dripping over the shoulders of his white

cricket pullover. The second leg

to go was the other fore-paw. Loud cheers. The boys now lacked proper handles,

so one of them grabbed the dog around the neck. Alas, one against two did not

work. The boy holding the head was just tugged away by the others. A second boy

now too grabbed the neck. A bitter fight ensued. But the neck proved no match

for two hind-legs. As the boys holding the head tumbled back, blood gushed out

over their well-pressed trousers. The head was tossed up in the air like a

ball, blessing the crowd with a fine sprinkling of holy juices. 'Ayubayubayubayubayub!

'Oaaaah! Oaaaah!

Oaaaah!' The students

holding the hind-legs were in a conundrum. There was nothing in front anymore

to hold on to. But one had a bright idea. They could just rip the hind-legs

apart and tear the animal open along the crotch. We did not wait for the

finishing touch but pushed our way out of the crowd. 'Ayubayubayubayubayub!

'Oaaaah! Oaaaah!

Oaaaah!' The next morning

Radio Pakistan announced that Field Marshal Ayub Khan had made some

concessions. Something about democracy. I believe it was more of it. The

general strike was lifted. Life, at least on the surface, returned to normal.

We booked seats on an express bus to Lahore and went to say our farewells to

Moussa Latif Jandial. We could not

help venting our disgust. 'Your students made quite a show yesterday, didn't

they?' 'What do you

mean?' 'A wonderful

symbolic action. They tore a dog to pieces. Right in front of the town hall.' He stared at us

not understanding. 'A dog with the

word 'AYUB' painted on its flanks. They quartered it.' He looked

appalled: 'This a dastardly act! I shall see to it that the perpetrators get

prosecuted.' 'You will?' 'I have powerful

friends. They will be very unhappy to hear that foreign writers have had to

witness such a disgrace. Who knows where this story goes. They should have done

this on an open field, well out of town.' For a moment I

thought I saw a mischievous twinkle in his eye. But that may have been just a reflection

of my own scepticism. Lahore was a relief, as all large cities are - if only because you can get

away from what you don't like. A city offers so many landscapes, so many faces,

so many moods, that you will always find a niche to be happy in. Apart from Tehran, which most everybody hated, Lahore, with over a million inhabitants, was the

largest of the Asian cities on the overland trail. It was also the cultural

capital of Pakistan. For those arriving, a foretaste of what India's big cities would bring, to those returning a place to linger before undertaking the

rough road back. There were some

two dozen other travellers in town. The term 'hippie' was well known among the

populace and you had three specific hippie-hotels. These were not in any way

geared particularly to European tastes. It was not like they served croque-monsieurs

and guacamole. They were simply middle-class hotels that had become popular

with Westerners because they offered relatively clean amenities, with showers

on each floor, fresh sheets for every new guest, and at least one English

speaker on the staff. Most provided room service. In the Rajah

Hotel there were six other Westerners, all on the top floor. Pakistanis of the

travelling classes hate the heat of upper floors (sticking to this prejudice

even in winter, when the climate is balmy), loath exercise, and are indignant

if they have to schlep themselves up even one story. We loved the views over

the old city with its flat-roofed houses, minarets and cupolas, and were quite

content to have the floor more or less to ourselves. There was considerable

mingling, and telling of stories. Flute was matched with drum, voice with

mouth-harp, silence with silence. We had long

regretted not having a good place to do our exercises. Most hotel rooms had been

either too small or too dirty and unlike many travelling Muslims, we did not

carry prayer-mats. Here we had the roof, and plenty of space in our room. We

bought plain cotton cloths that could be washed and dried in minutes to spread

on the tiled floor. We exercised, meditated and stood on our heads for one

hundred breaths, staring into each other's eyes or into the starry space

inside. The hotel

provided padlocks, but like all Asian travellers of a certain worth, we carried

our own, a Swedish brand bought in Istanbul. It was a good lock. We found this

out when Ewald, our hakim, our key-keeper, one day managed to lock us

out. We notified the management. Did they have someone who could get it open?

Soon a soiled man in shorts and singlet arrived with a screwdriver and a

hammer. Uninformed about the construction of cylinder locks, he attempted to

insert the screwdriver. The next ten minutes he tried banging the lock open,

bending the door's steel fittings and hacking dents into the woodwork. 'This is not a

Pakistani lock', the man said accusingly. We had to admit this. 'We shall need

special saw.' 'You have one?' 'No, you pay, I

will get.' An hour later

our man was back with a rusty old iron-saw. He went to work with confidence.

After five minutes I bent over to inspect his progress. Not a scratch. The

chromium-steel shone defiantly as if it came straight from the factory. 'This is not a

Chinese lock', the man said. We had to admit our blunder. Why did we have to

buy such a superior lock? A couple of pigeons came to rest on a ledge, enjoying

the action. 'I will fetch

locksmith. You have to pay. Maybe fifty rupees.' It seemed a bit

steep. A good locksmith might make five hundred a month. 'How about

twenty?' 'Yes, twenty is

fine. No problem.' We had offered too

much, apparently. Ten probably would have covered the expense, with at least a

rupee in it for him. A rupee bought you a basic meal in one of the restaurants

near the station. Two-fifty got you a repast with several curries, rice, fresh

baked flat breads, yoghurt, pickles and a sweetmeat for desert. (The bank gave

9 rupees for a dollar.) After an hour

there arrived a thirtyish man whose predilection for butter-based sweetmeats

had severely impaired his upward mobility, and what looked like a frail fifteen

year old but was probably a twenty year father of three. They had a clear-cut

division of labour. The heavier man stuffed his cheeks with betel and

rested his frame on the veranda, the other attacked our lock with a heavy-duty

iron-saw, initiating a fierce screeching that sent the pigeons sky high. After three

minutes the man whose duty it was to chew betel became restless. 'Jeldi, jeldi!' he called out, as if he were speeding up a donkey. From now on he

repeated this every minute, an extension of his task that he suffered with

sighs of exhaustion. The young man

took another ten minutes to get through the Swedish steel. Then he proudly

showed us the fruits of his destructive effort, not just taking off the lock,

but throwing the door open wide, as if display of the unlocked space amplified

his performance. The chewer pocketed our twenty, slipped the hotel-technician

some coins and bounced down the stairs laughing like a hyena. Lahore had an American Express office. It was a popular place to go for doubling

your money. Robert, the single traveller in the room next to ours, explained

how it worked. 'You go to the police, tell them that you lost your cheques, get

them to write up some statement (you may have to bribe them, they're not

stupid) take it to Amex and get yourself a new set of cheques issued. Don't try

to exchange the old ones in a bank, they get lists of cheques reported stolen,

but take them to the black market. You get a better rate there anyway.' When we went

over to the office to check out the atmosphere, they were just processing two

cases of theft. One boy, who claimed to have lost $80 got a refund on the spot.

A French couple who were going for the big one, with $1200 mysteriously stolen

from their locked hotel room, were told that American Express wished to await

the results of the police investigation. 'How long will

that take?' the boy asked. 'Three to four

weeks,' the manager replied. The girl took

this information badly. 'My ass', she told her companion in argot, 'I'm not

going to wait in this fucking city for a whole month.' 'But it's a lot

of money', the boy tried. 'And we could double it again in India.' The refund

manager, a young Pakistani, perhaps five years older than his esteemed clients,

looked on as the discussion unfolded, resigned to his non-understanding. 'Go jack off,

it's my money anyway. I'm out of here.' She got up and

stomped out of the office, supposedly dead broke. The boy apologized to the

manager: 'Sorry, there is a misunderstanding. She says she may have hidden it

somewhere and forgotten. We'll have another look.' 'That's fine',

the manager said, stuffing his papers in a folder. 'So you are withdrawing your

application for a refund?' 'She's crazy',

the boy said as he got up. 'Ah yes, no

problem. Too many crazy people.' 'I may come back

tomorrow.' 'Yes, you come

back any time, no problem. Easy to renew the application. We have your passport

number and everything on file.' He waved the folder. 'I withdraw that

application. Let me have it.' 'No, we keep on

file. Better for you, more convenient next time.' 'Fuckin' cunt',

the boy mumbled in his juicy lingo as he walked out the door. 'Fuckin', fuckin'

cunt.' I had and still have

a high regard for the French and their culture, but it was hard to maintain

that on the road. Along with the Italians they were the worst cases. The filthiest,

most unsavoury bunch. Not that you wouldn't meet nice, clean, bright Frenchmen

- they could be the most entertaining and inspiring people - but when you saw a

hippie with needle sores down his arms, or one who went begging, it was a safe

bet that they'd be French. To hear them cry 'Baksheeeeejjjsh sahib,

baksheeeeesjjjsh' with a French accent and French theatrics is something to

be experienced. Some wound rags

around their limbs to suggest a debilitating affliction, but their voracious

junkie faces with those hollow, feverish eyes often sufficed to elicit sympathy

from the Pakistanis, particularly the older generation, too steeped still in

respect for Europeans to grasp that they were being exploited. One young

Pakistani in the neat white clothes of an office clerk had a more modern

response. He walked up to one of those Latin mendicants, delved in his pockets

and, with a contemptuous smile, handed the sufferer a coin worth one tenth of a

dollar cent. 'Fuck you, man',

the Frenchman called after the Pakistani. The young man

turned around: 'Don't say like that! You are only guest in this country. If you

do not wish to be humiliated, you are free to go.' 'I have no

money.' 'Then why you leave

home? You think there is more money in Pakistan?' 'I came to study

your culture.' 'Ah, but then

you have learned nothing. Our culture is not to be dirty and use dirty

language.' 'Come on, give

me a few rupees. I need money to get home.' 'Why don't you

ask other foreigners. They have plenty of money.' 'I've tried.'

(Probably true, they were always out to wangle some money, 'for medicine', 'for

a ticket home', 'to feed my monkey'.) 'You know what

you should do? Go and start walking! If tonight I see you again, my friends and

I shall give you a good hiding.' 'Fuck you, man.' 'Yes, fuck you

too.' The Pakistani

sounded uneasy, as if he said something as crude as this for the first time in

his life. Even in this setting, where the Oriental was the upper dog, the cultural

transfer went from West to East. Over the years there

have been consistent attempts in the media to depict the 'hippies going to India' as a bunch of confused dope-heads. Though I will not deny that a number might

fittingly be so described, they were the fringe. They tended to congregate in a

few favourite spots and not stray far from the path between them. Some simply

commuted between Kathmandu for the summer and Goa for the winter. The majority

were - unlike the journalists describing them - young people who had achieved

something early in life and had the possibility to take off for a year or two -

or indefinitely. And moreover, had the courage to do so. Some had just

graduated but weren't ready to go for the big house, the big mortgage and the

house full of crying babies - not just yet. Others had dropped out for good,

seeking a more meaningful way to develop their talents, or a more feeling way

to live. Rock musicians who made a couple of hits but couldn't see themselves reduced

to pluggable products; writers and aspiring writers; people deep into Vedanta

or Buddhism who studied Sanskrit or Pali; psychologists seeking inspiration

for the developmental thinking that was to shape the movements for self-improvement,

non-competitive education and wellness that are still blooming (and becoming

big business); journalists who had escaped the daily or weekly deadline; anarchists

and world citizens who found a super way to stay off the grid; boys who did not

want to go to Vietnam but went to Laos instead and came back love-sick; Aussie

students on the way overland to England; girls who had sold their boutiques on

King's Road or opted out of modelling and scoured the villages for antique

jewellery and textiles, meeting the women in ways we never could; budding

experts on any and all fields. So when you

happened to run into each other at Jehangir's or Anarkali's Tomb, in the Shrine

of Mian Mir, under the cool arches of the Fort, or on the immense open square

of the Badshahi Mosque, there was no sense of intrusion, of being hindered in

your private enjoyment. On the contrary, it was encouraging to see other

people of your own age who had made it out this far and looked happy and

healthy. As no one published budget travel guides yet, their rave reports on

other places to go were essential information - as were alerts to bureaucratic

hassles and popular rip-offs. The most idyllic

place to meet was the Shalimar Gardens, a short taxi or a long rickshaw ride

out of town. (Now it is right in the middle of it, a middle class area.) This highly stylized park of eighty walled-in acres was laid out

in 1637 by Shah Jahan, one of the most illustrious Mughal emperors, builder of Delhi and the Taj Mahal. Across three staggered terraces with manicured lawns and white

marble pavilions, water flowed through white marble channels, feeding a large

tank crossed with white marble pathways, and three-hundred large and small

white marble fountains. The effect is so romantic as if it has been carved out

of white chocolate, but the styling so restrained that it is not sentimental. It

is just unbelievably beautiful. The beauty was

not lost either on the Pakistanis who flocked here on Sundays. The superlative

elegance of the surroundings gives them a heritage to be proud of. It gives

them something more basic too. In a land such as this, where water is scarce,

to see so much of it in one place, spouting up in a continuous display of

plenty, makes the people gay like children. In few places on earth can you see

so many folks smiling, laughing, playing and looking at each other amorously. To me, the Shalimar Gardens held a special attraction. Five years before in a jazz club I met a young

bass player and a drummer I had been to primary school with. In the alley

outside we managed to score some grass. As smoking it inside was forbidden and

the streets were not safe, we decided to save the enjoyment till after the show

and go to the bass-player's pad. It was a long walk through the night. When we

arrived we were exhausted. We smoked some of the grass and found it more powerful

than expected. For a long time

we lay flat on our backs. Wasn't there any music? Yes there was a portable gramophone

and also one record. It had a beautiful cover: a drawing of an Oriental formal

garden with white marble kiosks, green lawns, and numerous fountains. The

record-player started and the room was filled with low, undulating voices that

seemed to come from the underworld and hummed endless, wordless notes. Two

baritones, constantly waiving around one another. Gradually a rhythm was

brought in, the sounds combined to words, the speed increased and fixed

patterns started to appear with infinite variations. A drum came in, hammering

patterns too complex to follow, with strange syncopation. But it had swing, a

lot of swing. It was a strange vocal jazz, performed with astounding intensity,

spontaneity and creativity. The music swelled and surged and finally spiralled

to a psychedelic climax. 'Wow!' 'What is this?' It was my first

Indian music. Pakistani music to be more exact. Classical drupad,

performed by Nazakat and Salamat Ali Khan. I was flattened. Nothing in Western

music combined that ecstatic climax and stylistic strength. You had Free Jazz

and you had Beethoven, but you didn't have this conscious build up of a trance,

from deep, slow awakening, to rapid, consciousness expanding excess. We stayed till

the first light in that room, with that single record. Tracing back the line of

my journey, back from this room where I write these words (as a Pakistani

singer, chosen not without intent, is singing in the background), back to India

where I performed for Baba Alauddin Khan, trying to play well enough so he

would not hit me with his cane, back to my apartment in Amsterdam with its

stacks of Indian records, I recognize that it all began there, with that

entrancing music, and that drawing of a heavenly garden. Seeing that same

image, but in real life, was trippy. It was as if I was walking into my mind,

section South Asia. It was more peopled now than in my mental image, with

extended Punjabi families, boys floating sail-boats on the tank and splattering

each other, girls with open faces, innocently joyful, running over the matte

white pathways, their flimsy veils fluttering in the wind, newly married

couples being photographed like parading royalty and elderly gentlemen on a

preview of heaven. Still, it was

easy to conjure up Shah Jahan reclining in one of the pavilions, listening to

the Ali Brothers' forefathers seated at his feet. You could hear the slow

build-up from silence into a meditation on the scale, the birth of rhythm,

filling you with expectation for the playful improvisations, the majestic compositions

and the ecstatic finale. It was in gardens like these that the foundations were

laid for musical dynasties spanning two or three centuries that shaped the

whole tradition of Hindustani classical music. As I was to

learn a year later, the real music is not made. It is the inner sound we carry

inside us. To make others hear it, we enter the material world and strike,

pluck, aspirate, blow or bang it. Equally, the

real book is not what you are holding, it is what I have had in my head these

twenty five years. Now I have gone into the material world and banged it. Lahore is practically on the border. It never was, of course, until in

1947 that line was drawn. It had always been in the centre of Punjab, capital

of a large and powerful state peopled by Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs. The Hindus

and Sikhs now lived on the other side, apart from a few, but their monuments

they had not been able to take with them. We went to visit

the shrine of one of the most important Sikhs gurus, Arjan Singh, the man who

wrote the Holy Book, the Adhi Granth. The building was in disuse; no one came

to worship here but two old priests and a family of rats. It was surrounded by

a tall barbed wire fence. The yard smelled of urine; it may have been the

rats'. The officiant who received us, dressed in a white robe and a blue

turban, a golden sword on his side, said that the wire was to keep people out

during the renovation. Much improvement was indeed needed, but there was no

sign of ongoing work. Could it be that the barbs served mainly to keep out

vandals? 'Yes, that too,

but it is not very effective.' He hesitated. Did not want to seem complaining.

'The government has promised better measures.' 'But the

government has made many promises.' The old priest

adjusted his turban. 'Yes, many promises.' 'It must be

difficult for you to live here.' 'No, not

difficult. We have our friends here.' 'But other

friends have lost their lives.' 'So many of our

gurus have equally given their lives. It would be a blessing to die defending

our temple.' There it was

again, that notion of the Holy War and the Holy Warrior. When will people see

that no war is ever holy? That no idea is worth killing for. That there is

nothing the brain can achieve that brings you closer to reality. It may be a

while. For many people the idea of a Truth is attractive. It is simple and

redemptive. Alas, it is also stupid. The belief in Truth is more dangerous than

the atomic bomb. One day we were

having tea in a coffee-house (they did not serve coffee) and sat reading some

of those abstruse tracts Pakistanis write, proving the authenticity of the hair

of Muhammad kept in the Badshahi Mosque by quoting people who attest to its

miraculous workings in cases of illness, barrenness and theft, or an analysis

of the three-hundred Qoranic reasons why women are subordinate to men. We were

joined at our table - freedom to join any table being one of the attractions of

the coffee-houses - by a small middle-aged man with a pale complexion, a round

face and thick glasses. He introduced himself as Mubarak Ahmed, poet. Though Mubarak

dressed conservative, his mental make‑up was radical. He wanted nothing

to do with authorities; could not even be bothered to fight them. His sources

of inspiration were nature and the gardens in the human soul, but he worked in

the post-office, in a dull grey department, with no one around him but sorters

whose only mind-content was the street-plan of the city. He told us that he had

many writer friends, but that ultimately, the poet is forever alone. Yes, we knew

that poet. The brushless one. The only bard worth listening to. We went out and

walked all through the town with him, Mubarak pushing his bike and excitedly

pointing out an interesting niche here, a good stationer there, a Kashmiri

restaurant with the town's best shami kebab, the house of a writer who

had been picked up one night and never heard of since, and the special

'Defacement Window' in his post office, where customers using high denomination

stamps could see them defaced before their eyes, assuring that they would not

be steamed off the parcels by postal workers looking for additional income. Over the rest of

our days in Lahore we kept seeing him, exchanged poems and told each other how

wonderful they were. Mubarak now and then managed to get one of his in the

newspaper and was working with a printer to publish his first collection. They

were not bad, but they weren't overwhelming either. Too many twittering bulbuls

and other stock fauna of Muslim poetry. Maybe they sounded better in Urdu. His

sentiments were pure though, and to be with him was like visiting a sweet old

grandpa, always concerned about your health and comfort and the quality of your

impressions. He was always

eulogizing. Everything that happened was beautiful, nothing too abject to

adore. Good and evil in perfect balance, never too much of the one or the other

- though, still a mere mortal, he did admit to the sin of a lingering preference

for the aesthetic. One of his more memorable lines was: "I see the beauty

of God everywhere, in the leaves on the trees, the faces of the people and the

garbage heaps on the streets - how can I keep from singing?' He took us to

the Lahore Central Museum and showed us a statue of Buddha so touching that it

was hardly material. Although I have beheld it only once, I see it before my

eyes as clearly as the second century artist must have seen it before he

whetted the chisel. A large figure in shiny black stone showing the fasting

Siddharta Gautama as an emaciated, but beatific young man, skin over bones,

every vein, every sinew standing out. You feel that this is as far as one can

go without leaving the body for good. The emaciation

is exaggerated, but only a slightly. He is still a man, who could be real. Like

Christ he has taken the burden of the world upon himself; unlike Christ he does

not struggle to shoulder, but to discard it. To look at him produces a deep

sadness about the human condition that causes the need for such intense ascetic

withdrawal - and joyous wonder about the power of man to overcome his

self-destructive urges and regain the bliss that is his by right. Mubarak invited

us over for Eid-al-Bakr, the festival at the end of the pilgrimage period, when

Muslims celebrate Abraham's treaty with God. Abraham was asked to sacrifice

his beloved son, but after he showed his readiness to do so, was allowed to

substitute a goat. (According to the Old Testament Isaac was the potential

sacrifice, but the Muslims, often more romantically inclined than the

legalistic Judeo-Christian tradition, maintain that it was Ishmael, the

love-child by Abraham's handmaid,

Hagar.) A goat, bakr, is slaughtered to

commemorate this pact. Part of the meat may be eaten by the family performing

the sacrifice, but most is supposed to be distributed to the needy. Mubarak must

mentally have ranged us either among his family or the destitute. When we

arrived, the slaughtering at his place had long taken place. I did not regret

it. We had seen animals being knifed and gutted all morning and the streets

were red with blood. The few sheep and goats that survived, smelling the life

juices of their relatives, stood shaking with fear and bleating horribly. Dogs

slunk through the neighbourhoods, licking at the red puddles and hoping to

find some scraps of skin with meat left on it or a lost piece of gut. The curry

was beyond reproof, but the meat was chewy. Maybe it was not dead enough. The poet left

further entertainment of his relatives to his wife and sons and went back

onto the streets, his Elysian fields. We walked three abreast, Mubarak pushing

his bike. He took it everywhere he went, like some men take their wives, but I

never saw him ride it. We walked along in silence, enjoying the spectacle of

Lahorese parading around in new clothes - prescribed for all who could afford

them - when suddenly he erupted: 'What is your program for tomorrow?' 'No program.' We had often

told him that we never had programs, that this was part of our process of

liberation. 'You are fooling

yourself, Sharif-ud-Din. You're program is to go to India. I just wonder how

much more time we have together.' 'We may leave

tomorrow, Mubarak.' 'Yes, and I will

never see you again.' 'Don't say that

Mubarak. You may. And we will write.' We did write,

and half a year later I composed a poem especially for him. Replete with

apricot blossoms, dancing rivulets and all the bulbuls he loved. It must

have sounded wonderful in Urdu. India was only

fifteen miles away and our destination, Amritsar, could be no more than

thirty, but to get there we had to travel some hundred fifty miles, as the road

between the two largest Punjabi cities was closed. The only open border

crossing along the entire eighteen-hundred mile frontier with India from the Arabian Sea to the Himalayas, was seventy miles to the South in the otherwise

insignificant village of Hussainiwala. To further obstruct travel, this road

crossing was closed to nationals of the two neighbouring countries. Only

citizens of third nations could pass. The neighbours themselves might visit

only by rail or air; if they managed to get both a visa and a ticket, neither

of which was easy. This stalemate continues to the present day. Too much blood

had been shed at this border for peace to return soon. In 1947, after the act of

separation was signed and the refugees started fleeing, the Muslims West, the

Hindus and Sikhs East, the Pakistanis slashed the throats and bellies of a

whole train full of Hindus, then sent the train across the border. When it arrived

in Amritsar, dripping blood onto the tracks, the Sikhs rounded up enough

Muslims to fill a train and sent them back the same way. It was merely one

dramatic interchange of many. In a few months time the mobs, those

bloodthirsty monsters, killed hundreds of thousands of people, guilty of no

more than being of the wrong faith or the wrong side of the border. The separation

from Mother India, the caesarian that gave birth to Pakistan has left an open

fissure that is still suppurating. Mother and daughter have gone to war three

times, and the Kashmir umbilical has never been cut. Before that work is done,

the sutures holding, many people may die, most in the gruesome manner inspired

by religious conviction. Shortly after

sunrise we took the bus to Hussainiwala, which dropped us at a collection of

tea-stalls just in front of the barrier. It was hard to see what they could

exist on. On an average day thirty people might come by here - all foreigners.

We got our exit stamps, strapped on our bags and lumbered the five hundred

yards across to the Indian side, our contraband this time stuffed deep in our

bags. If they start searching, the story was, you pull out your wallet. For

anything up to a few kilos, give them a nice taste and ten dollars. Should they

ask more, bargain down. We had covered

half of the five hundred yards, a strange calvary along a strip of cordoned off

asphalt, when suddenly I realized: you are about to enter India! The undramatic bus trip from Lahore had made it all seem so casual, but here I was,

only a few hundred steps away from the country that half a year earlier I set

out to reach. I looked ahead and waved at the Indian border guards, who smiled

and waved back. It was then that

I heard the uproar behind them. The mob? There too? We saw nothing threatening

and kept on going, sweating like coolies. 'Good morning.

Welcome to India. You carry any contraband?' 'No sir.'

('Sir', we found out in Pakistan, worked wonders.) 'Any cameras,

tape-recorders, or radios you want to sell?' 'No sir.' 'You want to

change money? I give you good rate. Better than bank.' 'No, thanks very

much.' 'Ah you have

Indian rupees already?' That was a

tricky one. You could not legally bring any in. But at American Express in Lahore they had been dirt cheap. The stack of notes sat uneasily in my underwear. 'No, but eh -

there must be a bank here somewhere.' 'Nearest bank is

in Amritsar. Too far. You need money for bus. Better to change here. Don't

worry I give you best price.' 'Alright, let's

do ten dollars okay?' 'As you like,

sir...' This expedited

our processing spectacularly. Another traveller sat pouring over stacks of

papers, all to be filled in quintuplicate, as our passports moved with great

speed across the various tables till at the last one we were given six months.

Stuffing away our papers we finally agreed to notice the dozen rickshaw drivers

behind the barrier who stood clamouring for our business, placed our bags in

the cycle of the man with the most pleasant face and started haggling for a

good deal to the bus station. We rode off